Недавно с моим другом, преподавателем догматического богословия, целый вечер спорили о том, хороша или нет «Новая перспектива» относительно апостола Павла. С его точки зрения, традиционная догматика (идущая еще от Ансельма и воплощенная у Лютера) неверно, слишном односторонне-юридически трактует искупление и оправдание, совершенно вне контекста самого Павла. Более того, и катихизис митр. Филарета, получается у него, здесь «неправославный».

А я пытался сказать, что такое понимание, тем не менее, не мешало людям становиться святыми, и, может, не в тонкостях понимания дело?

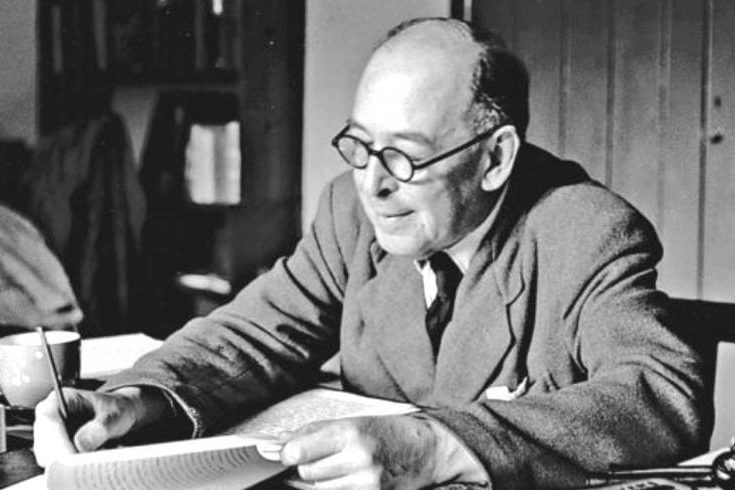

И вот, У К.С.Льюиса — письма как раз в период его обращения. Здесь еще хорошо о связи христианства и языческих мифов.

to Arthur Greeves: On the intellectual turning point of his conversion—myth become fact (see God in the Dock for the essay “Myth Become Fact”).

18 OCTOBER 1931

What has been holding me back (at any rate for the last year or so) has not been so much a difficulty in believing as a difficulty in knowing what the doctrine meant: you can’t believe a thing while you are ignorant what the thing is. My puzzle was the whole doctrine of Redemption: in what sense the life and death of Christ ‘saved’ or ‘opened salvation to’ the world. I could see

how miraculous salvation might be necessary: one could see from ordinary experience how sin (e.g. the case of a drunkard) could get a man to such a point that he was bound to reach Hell (i.e., complete degradation and misery) in this life unless something quite beyond mere natural help or effort stepped in. And I could well imagine a whole world being in the same state and similarly in need of miracle. What I couldn’t see was how the life and death of Someone Else (whoever he was) 2000 years ago could help us here and now—except in so far as his example helped us. And the example business, though true and important, is not Christianity: right in the centre of Christianity, in the Gospels and St. Paul, you keep on getting something quite different and very mysterious expressed in those phrases I have so often ridiculed (‘propitiation’—‘sacrifice’—‘the blood of the Lamb’)—expressions which I could only interpret in senses that seemed to me either silly or shocking.

Now what Dyson and Tolkien showed me was this: that if I met the idea of s acrifice in a Pagan story I didn’t mind it at all: again, that if I met the idea of a god sacrificing himself to himself . . . , I liked it very much and was mysteriously moved by it: again, that the idea of the dying and reviving god (Balder, Adonis, Bacchus) similarly moved me provided I met it anywhere except in the Gospels. The reason was that in Pagan stories I was prepared to feel the myth as profound and suggestive of meanings beyond my grasp even though I could not say in cold prose ‘what it meant’.

Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened: and one must be content to accept it in the same way, remembering that it is God’s myth where the others are men’s myths: i.e., the Pagan stories are God expressing Himself through the minds of poets, using such images as He found there, while Christianity is God expressing Himself through what we call ‘real things’. Therefore it is true, not in the sense of being a ‘description’ of God (that no finite mind could take in) but in the sense of being the way in which God chooses to (or can) appear to our faculties. The ‘doctrines’ we get out of the true myth are of course less true: they are translations into our concepts and ideas of that which God has already expressed in a language more adequate, namely the actual incarnation, crucifixion, and resurrection. Does this amount to a belief in Christianity? At any rate I am now certain (a) That this Christian story is to be approached, in a sense, as I approach the other myths. (b) That it is the most important and full of meaning. I am also nearly certain that it really happened.

to Arthur Greeves: On why Christianity doesn’t appeal the way Paganism does; and on the spiritual danger of looking for an encore (see Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, 27 and 90).6

8 NOVEMBER 1931

I, like you, am worried by the fact that the spontaneous appeal of the Christian story is so much less to me than that of Paganism. Both the things you suggest (unfavourable associations from early upbringing and the corruption of one’s nature) probably are causes: but I have a sort of feeling that the cause must be elsewhere, and I have not yet discovered it. I think the thrill of the Pagan stories and of r omance may be due to the fact that they are mere beginnings—the first, faint whisper of the wind from beyond the world—while Christianity is the thing itself: and no thing, when you have really started on it, can have for you then and there just the same thrill as the first hint. For example, the experience of being married and bringing up a family, cannot have the old bittersweet of first falling in love. But it is futile (and, I think, wicked) to go on trying to get the old thrill again: you must go forward and not backward. Any real advance will in its turn be ushered in by a new thrill, different from the old: doomed in its turn to disappear and to become in its turn a temptation to retrogression. Delight is a bell that rings as you set your foot on the first step of a new flight of stairs leading upwards. Once you have started climbing you will notice only the hard work: it is when you have reached the landing and catch sight of the new stair that you may expect the bell again. This is only an idea, and may be all rot: but it seems to fit in pretty well with the general law (thrills also must die to live) of autumn and spring, sleep and waking, death and resurrection, and ‘Whosoever loseth his life, shall save it.’7 On the other hand, it may be simply part of our probation—one needs the sweetness to start one on the spiritual life but, once started, one must learn to obey God for his own sake, not for the pleasure.

to Arthur Greeves: On the theories of the atonement (see Mere Christianity, Book II, Chapter 4)

6 DECEMBER 1931

As to [your cousin] Lucius about the atonement not being in the Gospels, I think he is very probably right. But then nearly everyone seems to think that the Gospels are much later than the Epistles, written for people who had already accepted the doctrines and naturally wanted the story. I certainly don’t think it is historical to regard the Gospels as the original and the rest of the New Testament as later elaboration or accretion—though I constantly find myself doing so. But really I feel more and more of a child in the whole matter.

Взято отсюда

Top bar menu

+7 926 526 37 39info@nasledie-college.ru

К.Льюис. Миф и понимание. Искупление и язычество (на англ.)

Вы здесь:

- Главная

- Мысли вслух

- К.Льюис. Миф и понимание. Искупление…